Along the Silk Road with Venetian Painters

Related Tours

Many Venetian paintings of the Middle Ages and Renaissance give us the chance to observe details of life in past centuries: architecture, glass, food, animals, and of course fashion.

The splendid fabrics depicted in the works of the Italian masters of the Gothic and Renaissance periods show mesmerizing patterns and rich colors; let’s take a closer look at some of the masterpieces in the Accademia Galleries of Venice to discover something about the luxury goods market in the past.

The Global Silk Trade in the 14th century

The Polyptych of St. Claire was painted by Paolo Veneziano around 1350.

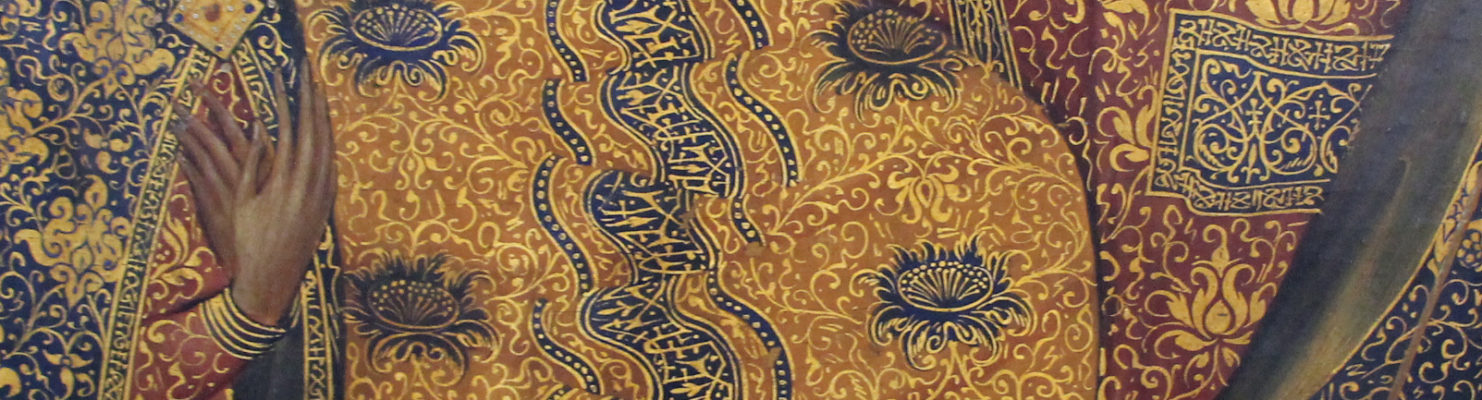

The central panel, showing the Coronation of Mary, is a triumph of gold, red, and blue: the colors used in the robes of Mary and Jesus. Through the beauty of their intricate patterns, these painted fabrics reveal the fascinating melting pot of cultures that marked the 14th century.

The robes depicted by Paolo Veneziano are known as panni tartarici (Tatarian cloths): silk textiles produced in the territories of the Mongol empire that found their way across Asia and were used in Europe as well. Clothes for the Mongol court were produced in different locations in China and Central Asia, and the workers were often forced to move from one factory to another, mixing motifs and techniques from China and Persia. Before reaching Europe, then, such precious fabrics had travelled through the territories of the Muslim powers in the Middle East, which explains the presence of Arabic inscriptions.

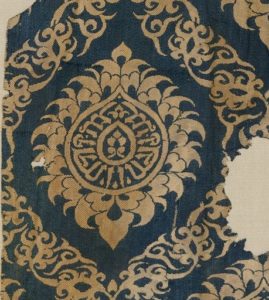

A set of three circles in a triangular shape is derived from the Buddhist chintamani (flaming jewel), a symbol of good luck that was also used in the Muslim tradition and became extremely popular during the Ottoman Empire.

Left: detail from Paolo Veneziano, “Coronation of the Virgin Polyptych”, 1350, Venice, Accademia Galleries.

Right: fragmentary silk velvet with repeating tiger-stripe and chintamani design, second half of the 15th century, Turkey (Bursa). From the collection of the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Intricate floral patterns like these were typical of the Central Asian craft that flourished under the Mongols and was exported to Europe.

Left: detail from Paolo Veneziano, “Coronation of the Virgin Polyptych”, 1350, Venice, Accademia Galleries.

Right: silk and metallic thread lampas, late 13th – mid 14th century, Central Asia. From the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Arabic inscriptions often found on fabrics became a source of inspiration for decorative motifs.

Left: detail from Paolo Veneziano, “Coronation of the Virgin Polyptych”, 1350, Venice, Accademia Galleries.

Right: silk textile fragment with ogival pattern, 14th century, Egypt or Syria. Repeated within medallions, in mirror image in Arabic in Naskh script:

السلطان الملك (The sultan, the king). From the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Nasij: the forbidden Golden Cloth

Many of the panni tartarici that reached Venice were woven with gold thread, and different names were used to define the different types of fabrics, depending on the weaving techniques and the amount of gold in them: lampassi, baldacchini, camocati, the list goes on and on. In fact, so many terms were used that it is difficult for us now to understand exactly what each name referred to, but one fabric type was described as the most expensive: the nasiccio, from the Arab nasij al-dhahab al-harir (cloth of gold and silk).

Nasicci were mentioned by Marco Polo and other merchants of the time, and they were described as the very fabrics used to make the clothes of the Great Khan himself. Venice, though, had no emperor, and the nasiccio was therefore considered by the government too expensive to be used by anyone in the Republic. A law from 1333 stated that no robe could be made with the fabric, with no exception for anyone, not even brides on their wedding day, who were normally granted some privileges by the sumptuary laws.

Although gold thread appears in most of the fabrics painted in the 14th and 15th century, only a few of these examples are similar to a nasiccio, and they are used only by saints or kings.

For example, in a painting by Vittore Carpaccio belonging to the St. Ursula cycle, the father of Ursula, the king of Brittany, is wearing a robe showing a very thin motif in red on a shining golden background. Although the pattern is similar to the ones on other robes, the quality of the fabric seems different.

Above: detail from Vittore Carpaccio, “Arrival of the English ambassadors”, 1490-95, Venice, Accademia Galleries.

Below: “Cloth of Gold” with medallions, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), 14th century, China, silk and metallic thread lampas. From the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Made in China, in Turkey or in Venice?

The skilled weavers from Venice and Lucca (many of whom had moved to the Venetian Republic in the early 1300s) soon started producing fabrics very similar to those which had originally been imported from Eastern lands. This Asian style influenced Islamic and European production so much that it is sometimes impossible to tell exactly where something was made: we are talking about an international trend spanning from Beijing to Granada!

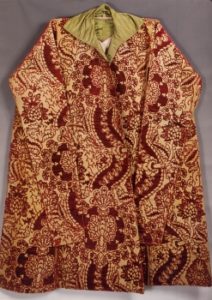

In the 16th century, the Ottoman Sultans actually preferred lampasses made in Italy to those made in Turkey. As a result, Venice was producing fabrics to export to the Ottoman court, but decorated with motifs influenced by the Asian style.

On the other hand, the Christian clergy often used Asian textiles for their ceremonial robes, mixing them with locally made fabrics showing crosses and images of saints.

Both for sultans and for popes, foreign fabrics were a symbol of luxury that only the richest could afford, and they were therefore chosen to display the wearers’ high status.

Left: Giovanni Mansueti, detail from “Episodes from the life of St. Mark”, 1525-27, Venice, Accademia Galleries.

The large canvas depicts a mixed crowd of Venetian and Muslim characters, the latter wearing clothes and headdresses in the Ottoman and Mamluk fashion.

Right: silk caftan attributed to Mehmet IV, produced in Italy; sewn and lined in Istanbul, Turkey, 17th century. From the collection of the Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul.

Above: Lazzaro Bastiani, “Offering of the Relic of the Cross to the Members of the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista”, 1495. Venice, Accademia Galleries.

Below: Ecclesiastical cape (piviale), produced in Turkey, probably Bursa; cut, assembled and embroidered in Venice, mid 15th century, silk, gilded silver thread. Venice, Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari.

The above details show Asian style patterns and Christian iconography on the capes of religious figures in different paintings (from left to right):

Lazzaro Bastiani, “Nativity scene with Saints”, 1480, Venice, Accademia Galleries.

Giambattista Cima da Conegliano, “Doubting Thomas with Saint Magnus”, 1504-05, Venice, Accademia Galleries.

Vittore Carpaccio, “Presentation of Christ in the Temple”, 1510, Venice, Accademia Galleries.

Had you ever imagined that so much history is hidden in the details?

A careful look at the masterpieces in the museums and churches of Venice is a great way to bring the fascinating past of this unique city back to life.